Ashneer Grover resigned earlier this week in advance of a Board Meeting where it was expected that his positions at the Company would be terminated. His Grover’s rapid rise and fall is part of a larger story playing out amongst founders and investors today. In this letter, I will explore how his story again brings to light a VC playbook that might have started opportunistically but seems to have found institutional design, and how this is causing havoc amongst startups and their founders.

The visionary CEO

You are a founder of a startup that is going places. You have raised millions of $ through multiple rounds, you have the best possible set of investors and you took things to the next level. The company is now much bigger than you - it runs on its own, has a market beating team and sales are going through the roof - hell, you can now holiday in far away islands while your team closes the company’s next big fundraise.

The dream startup founder who gets to this place, and fast, right? The press is counting the billions are you are worth and your investors are patting themselves on their backs for having found you.

That’s when you discover that things are suddenly going wrong for you and really fast. The carpets are being pulled from under you and everything seems to be at stake.

You feel like Ashneer Grover is feeling today. But he isn’t the only one.

Magic of founder equity

Going back to the beginning. When you started the company and it grew, you were indispensable to the operation. Investors look for great founders because founders take the company from “zero to one”. When you are doing this job, you are central to the company’s future. This is why investors are happy letting you hold equity for which they pay premium prices.

You are told (and you know) that the success and growth of the business, and your wealth creation depends on your ability to make yourself less relevant as time goes. You want to be that founder who has built something that drives itself to new highs while you retire to reap the benefits. Well, this is also in the best interests of your investors and other shareholders - for another very special reason. The company is no longer dependant on you, which means also that your investors are also less dependant on you.

From the investors perspective

Let’s break this up into general principles in a way that someone investing in your company has understood after investing in several companies like yours:

Holding or obtaining more equity in the companies that succeed is the only way of adding value to a successful investment after it has been made.

The more equity the founder holds when an exit/liquidation/sale event occurs, the less the investors make.

The more influence the founder has on the company’s affairs, the less the investors make.

Therefore, if you want to be a successful investor, you need a playbook for companies that succeed. A playbook that allows you to reduce the founders equity and influence, so that you make more on the investment. You get paid for doing this work, this is a key purpose of your existence, your limited partners (investors) depend on your acumen in being able to pull this off as much as possible and as often as possible.

Reducing a founders equity

The way to set the ground for this is to have the following ingredients in the documents you sign the founder up for when you invest - (a) a right to buy the founders equity at nil or low value if x, y and z happen; (b) x, y and z should be stated in broad terms and include highly subjective evaluations.

How this is accomplished is by having provisions in the contracts that “clawback” founder equity, i.e., set out the principle that the founder is earning her equity over a specified period, say 3 years. During this period, if the founder is “caught” doing certain things then the founder can be fired and equity for the “unearned period” bought up by the investors. Sounds fair?

Here’s where things get dicey. Outside of those who do obviously criminal things like put their hands in the cookie jar and steal from the company, founders rarely do things that damage the business - we are after all talking about companies that are winning. This is why the x, y and z should include things that allow you to go after founders that aren’t damaging the business. How do you accomplish this?

Let’s look at a common example, also found in Bharatpe’s shareholder agreements that determine the conditions under which Ashneer Grover can be terminated from employment and a portion of his shares taken away:

“gross negligence or wilful misconduct by such Founder, as determined by a Big 4 Firm, which does not have any relation with the Company, after which the Board shall, through a simple majority, take a decision on such Cause event based on the report shared by the appointed Big 4 Firm after following principles of natural justice;”

Gross negligence and wilful misconduct as determined by a consulting firm (with no relation to the company, but probably a good relationship with the investors). Sometimes, you will also find more wishy-washy sounding conditions - insubordination, absenteeism, involuntary exit, resignation, misrepresentation and other serious sounding but highly subjective legal terms added on to the criteria that will determine whether you can be “terminated for cause”. This kind of termination “for cause” might also be linked to the loss of your other rights in the Company, such as being able to appoint a director on the Board, thus further reducing your influence in the company. If the criteria is met and process followed, your investors get the right to accomplish their objectives in the following ways:

Terminate you from employment and reduce your influence on the affairs of the company.

Argue that only a specified period of your “clawback period” applies to when your conduct was kosher, and for the rest of the period, they are able to buy a proportionate number of shares at nil value.

Kick you out of any other positions that allow you to influence the company, such as the board of directors and reduce the amount of information you are able to obtain on the affairs of the company.

Ashneer cornered

Lets snap back to the provisions of the shareholder arrangements that Ashneer Grover is subject to. Here is what they say:

“If the Company terminates a Founder’s employment for Cause with the consent of Investors representing at least the Majority Investor Threshold or if a Founder terminates his employment for reasons other than Death or Permanent Disability, unless such termination has the approval of the Board and the Investors representing Investor Majority Threshold, then, subject to compliance with Applicable Law, at the option of the Board with the consent of Investors representing at least the Majority Investor Threshold, (i) the Restricted Shares held by such Founder shall be: (x) bought back by the Company at the lower of the FMV or the price paid by the relevant Founder for acquisition of such Restricted Shares; or (y) Transferred to an employee welfare trust at the lower of the FMV or the price paid by the relevant Founder for acquisition of such Restricted Shares; or (z) acquired from the relevant Founder in any other manner as the Board, with the consent of Investors representing at least the Majority Investor Threshold, deems fit at the lower of the FMV or the price paid by the relevant Founder for acquisition of such Restricted Shares.”

Having engaged a Big 4 firm, which acts as the judge and arbiter in connection with Ashneer’s conduct, which has provided a “report” to the Board which is bent on acting on it, Ashneer has lost the fight even before it started. The agenda of the Board meeting (where a majority of investors have made up their mind to remove him) would have indicated to him that “termination for cause” is happening at the Board meeting. As you will see in the way the provisions are drafted, the consequences are no different if he resigns without the approval of the Board, as he has done. Do not be surprised if the resignation is deemed invalid because the “termination for cause” is effective on a back-dated basis. This is speculation in this case but true in many other cases, and here is how the playbook would work.

Playbook in operation

5% of Ashneer Grover’s shares plus management pool are subject to a clawback period that starts September 2019 and ends September 2022. It isn’t unlikely that the Investors would be able to remove Ashneer Grover, say effective October 2021 - by claiming that his “wilful misconduct” commenced then they might be able to take away 25% of his equity, ie get equity for nothing. As opposed to say, recognising the resignation which is occurring in March 2022 which would still entitle a clawback but for a lesser percentage. This is a company that is already on auto-pilot with a successor management. At the time he signed on to it, the clawback might have been justified as necessary to protect from “moral hazard” and what is a 3 year commitment?

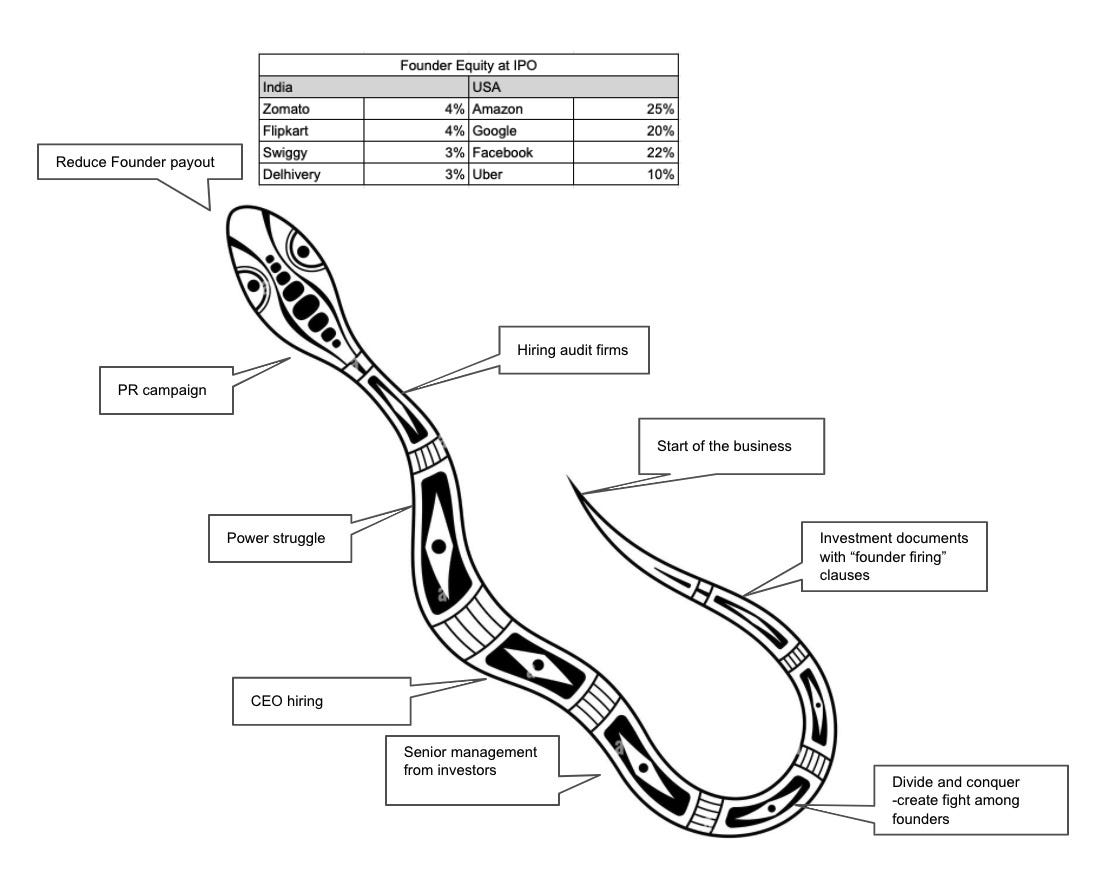

You might say, hey, what is 25% of 10% in the company distributed among all investors amount to? If every investor is getting 2.5% more than they for paying nothing plus reducing the founders influence in the company, letting them drive the exit, what could be better? This is after all a unicorn, small percentages amount to considerable value. Not to mention - the playbook would demand it. In other cases, where founders hold more equity, or where the clawback is more aggressive, the returns on this strategy are higher.

The moment you have invested your $ in the startup, your job now is to keep a close eye on the founder and do two things: First, build a “file” on any conduct transgressions or management issues, they might be trivial but conduct is proved by adding many trivial things into a indefensible whole. The criteria are sufficiently subjective and you have a friendly arbiter in a Big 4 accounting firm. You harangue the founder with legitimate sounding questions on management and conduct. How could you have hired this employee? How could you have signed this document? Why didn’t you seek the board’s approval for this? While managing a high growth company, mistakes are many but from a business perspective - all a part and parcel of running any business. Meticulous records and legal argumentation can turn a story of running any business into “gross negligence and a pattern of misconduct.”. The file is prepared, the founder is sometimes subject to some soft threats (to put things on record), but the knives aren’t out yet.

This brings us to the second step, finding the right opportunity. A weak moment is usually what you are looking for - for instance, the founder is embroiled in something unconnected to the company but under fire, is undergoing health or family problems, there has been an employee accusation or HR crisis. That’s when you move in with the file, and start laying out your case for “terminating the founder’s employment for cause”.

Work don’t get done if you don’t get your hands dirty

This fight might be dirty, he might go to court or he might buckle and settle quietly. Your team is ready for these eventualities as well as keeping the pressure on. Involving the other investors and getting them behind you is important but rarely difficult. We argue he behaved badly, it isn’t damaging the company, but we use this to damage him and enrich ourselves in the process - what is there to debate about?

Once you are able to remove the founder from employment and/or keep her busy with legal battles to preserve turf, no matter which way things go - you are setting the ground for taking away control from founders at the time of the exit. In a company where the founder has made herself irrelevant and the company is doing well, you know you don’t need the founder to get your payday when the company is sold. If anything, the founder is trouble - more information to play with on the inside, he might keep a closer watch on any side deals you make with an acquirer or confuse the acquirer into thinking he is important enough to grab a greater portion of the sale price.

On the other hand, it does cause some flutters when the founder is removed, there might be bad press, there might be a shadow on the stock price, there might be HR challenges, there might be litigation. In fact, what the founder did (or didn’t do) might be less damaging in the short term than your actions of removing the founder from the company. You have to be prepared to weather it out - the returns are outsized for these minor irritations that you have been hired to handle.

You also follow this up by taking actions to remove the founder from the Board of Directors (or attempting to do so), reduce the amount of information that is shared with her, and appoint new CXOs who have no relationship with the founder. Over a period of time, you are able to ensure that the founder is an outsider, you are the insider and any sale of the company has you leading from the front. That’s how you stand a chance to make the most, and ofcourse, at the expense of the founders.

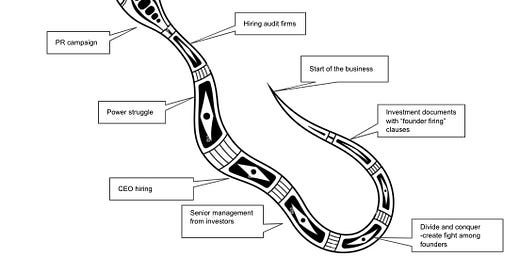

Here’s a ‘snaky’ graphic one of my VC-backed founder friends created to capture the logic of the playbook.

Fighting the good fight?

So where does that leave you the founder? There are only two ways you can protect yourself. The first would have been when you signed up your investors. By having understood what you signed up for, and even better having negotiated them around. If still, your conduct has a bearing on your ownership of shares, remember all of that might be up for grabs, and especially if your company does well. The more quickly your docs allow you to be booted from the Board or made less influential, the faster your demise. The second and more relevant for those of you who have signed up for these unfortunate terms - be prepared to fight hard and fight dirty when you are at your lowest point and everything might be at stake. The battle will be legal, social, emotional, reputational, financial - all at once. Bring out the knives.

This is not to say that there aren’t terrible situations where investors are being robbed in daylight while so-called founders suck up confidence in startup investments. These are legitimate corporate governance problems that investors should seek recourse at the expense of founders who have deceived them. The problem however arises when investors hide behind corporate governance PR to execute what are effectively institutionally designed unjust enrichment strategies aimed at taking wealth away from founders (and sometimes - employees as the ESOP pools are even more vulnerable). Because the playbook has been deployed widely and institutionally, there is hope that things balance out over time. Until then, there will be many more ugly fights of the Bharatpe kind and at the same time - neither is Ashneer Grover the first nor the only founder who has one his hands.

P.S: For those interested in a more detailed study of founder termination/clawback provisions, here is a copy of Bharatpe’s Articles of Association (Clause 97 and definition of “Cause”). This is a widespread model foretelling intimidation, here are for instance Snapdeal’s documents with a similar framework for termination of founder for cause and clawbacks. Given how widespread, I am aware of many shareholder agreements now being litigated by founders and “the quiet settlement” mode of operation might be receding into the past, in short, things are getting dirtier and uglier as the playbook is used more frequently.

A note of thanks to law students - Vedant Sinha (NLU, Assam) and Bhavisha Sharma (NALSAR) who were kind enough to pitch in with some of the research required on short notice for putting this together.

wonderful piece. Keep it up.

What a timely and wonderful piece, Suhas! I really hope more lawyers explain how transaction documents play out. Thanks!